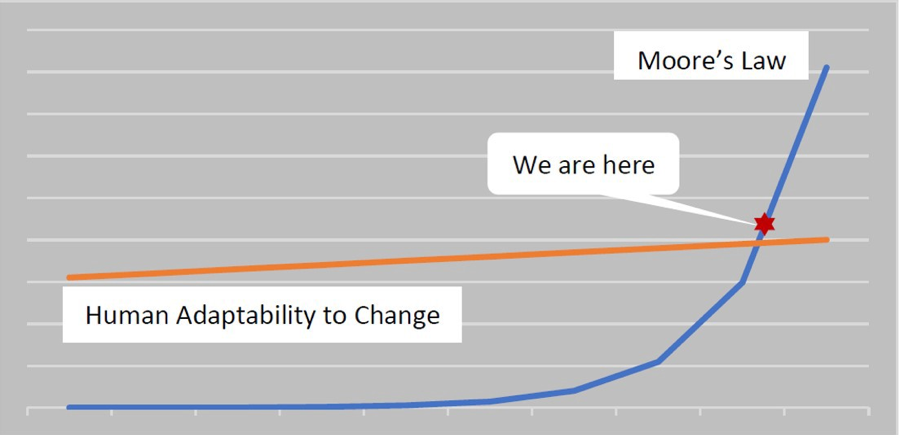

It doesn’t matter whether you hurray or boo for Donald Trump. Either way, you might be missing the bigger picture. Read Thomas Friedman’s latest book “Thank You For Being Late” and you’ll find below graph that explains, in one simple picture, the polarization, the frustration, the volatility, and the enormous change we are seeing in our world — and why the election of Donald Trump is simply a logical consequence of these changes. Astro Teller, Google’s Captain of Moonshots (CEO of Google X), scribbled this graph on a piece of paper during an interview with Friedman. One line illustrates Moore’s Law, the other one our ability as humans to adapt to change:

In 1965, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore predicted that the number of transistors on a microchip — and with that its performance — will double approximately every 18 months. Were you listening to Moore at that time, you might have just turned to him with a shrug: “Go for it, Gordon. Sounds good.” But, like many of us, you would have missed the profound implications of this statement.

We have barely entered the second half of the chess board.

If you put one dollar on the first square of a chess board and double the money on the next square, you’ll have 128 dollars by the end of the first row. Not a big deal. But now, 52 years have passed since Moore established his law, we are 35 squares into the chess board. Suddenly the numbers get big. Really big. Starting with one dollar on square one, you would have to place about 34 billion dollars on today’s chess square. And we have barely entered the second half of the chess board.

Intel CEO, Brian Krzanich, translates what this means for business — specifically the automotive industry — in his speeches. Comparing a 1971 VW Beetle with Intel’s first-generation processor (4004), and improving the VW at the same rate as Intel improved its processors, you would today have a Beetle that can drive 300.000 miles per hour, had a fuel efficiency of two million miles per gallon, and which would cost you four cents to purchase. You would be able to ride your Beetle on one tank of gas for your entire life.

Moore’s Law has pushed us into a world which no one of us is familiar with. Nobody — no government leader and no corporate executive — has been confronted with this rate of change, before. Moore’s Law has pushed us into a world, which changes so fast that virtually overnight AirBnB became the largest “Hotel” company, UBER revolutionized the transportation industry, Netflix became one of the largest film production studios, Amazon took over the business of century-old corporations, GitHub shape-shifted the way software is developed, Tesla created a new playing field for intelligent energy solutions, and on it goes.

As you consider these developments, you’ll realize that even globalization is to a large extent driven by digitalization — by Moore’s Law. Organizations are only able to effectively operate globally since the world-wide web, cell phones, and the supporting communication software became available. Global flows of talent, including outsourcing, are only possible in a digital world.

How does your mother use her smart phone?

Compare that to the second line in Teller’s graph: our ability as humans to deal with change? Research shows that, as long as it comes down to small changes — such as changing seasons, switching to different routines in a job, or becoming used to new airline baggage policies — humans are highly adaptable (after going through our initial resistance hissy-fit). But when bigger changes are on the horizon, which challenge our values and the way we see the world, our ability to deal with change is slow. Very, very slow compared to Moore’s Law.

Just consider how you use technology, how your mum or dad uses it, and how your children use it. My Dad owns a laptop. He bought it in 2002, so it’s now 15 years old. Since then, I have received two emails from him. Every time he’s done using his computer, he puts it back into the shelf; upright, just like a book. I, on the other hand, am quite confident juggling all of my tech gadgets. Until, of course, I walk into a room filled with millennials.

The time frame in which humans adapt to large-scale changes has improved, but only marginally. From one generation, or about 25 years, to maybe 15 years, today, Friedman writes. And now, we are at a point in history where both lines in Teller’s graph — Moore’s Law and our ability to deal with change — have crossed. And even though they have only just intersected, we are seeing a shit storm in our world that no one knows how to deal with.

We hear from organizations that their biggest concern is not to get “UBER’ed”. Corporate executives are pressed to create organizational cultures where millennials actually want to work — where people are self-managed, agile, and innovative, instead of being slowed down by long-winding decision processes, hierarchies, and political maneuvering.

Every one of us can feel Teller’s graph impact our daily lives. In our professional lives through the constantly increasing pressure, speed and complexity. And in our private lives maybe by the challenge of losing a job, or by the new convenience of ordering a taxi on your cell phone and knowing exactly when it will be there to pick you up.

For you as an individual, for organizations, and for countries alike, the question is: how do we deal with this new world order?

How to deal with the new world order.

We have three different options to cope with this challenge. No matter where you look, you can find these play out: in governments, businesses, and maybe even in your own family.

Strategy One: Step on the Brake. Individuals choosing this strategy essentially try to throw a wrench into Moore’s Law and slow down the speed of innovation, because they can’t keep up. Clearly, this strategy will not work as long as other organizations or countries choose to benefit from Moore’s Law. In a globally connected world, we can’t just get off the carousel. History shows that we may be able to delay evolution — we can isolate ourselves from the world, like Japan did from 1641 to 1853, or try out a socialist regime for half a century, like Russia or Cuba — but we cannot stop evolution.

And yet, that’s exactly what some of our world leaders attempt to do. In organizations, this might mean to tighten the thumb-screws, set higher sales targets, and squeeze cost. Don’t ask. Just do it. On a global scale, Brexit, Trump, or Turkey’s Erdogan are other examples for this strategy — supported by voters who might have been told at the age of 18 that if they just learned a good trade, they will be able to keep a solid job for the rest of their lives.

Many of these individuals have not been able to grow with our digitized world and just want to throw a wrench into Moore’s Law. “Making America great again” is not likely to work, because the jobs these individuals have trained for are unlikely to ever come back.

Strategy one: to step on the brake, is essentially like driving down the freeway by looking into the rear mirror.

Strategy Two: Deal with the Challenge. This is the strategy most organizations seem to adopt. The mantra is rather straight forward: enable employees, re-train leaders, and create more engagement and ownership in teams to enable the organization to become more innovative, flexible, and adaptable.

The reason why this strategy will not succeed, either, is this: leaders who are choosing this approach still see the challenges ahead as a problem that needs solving. With this problem-focused consciousness, these organizations and their leaders will remain reactors, maybe even victims to the challenges and changing environment ahead of them. They will always be a step behind. They will never be leaders.

Strategy Three: Be the Innovator. If you examine UBER, Facebook, AirBnB, Amazon, or even Apple, they don’t see digitalization as a challenge. On the contrary. They are having a field day, because they are positioned to ride the wave. They are the ones reshaping and redefining the way we work and live (without a judgment whether this change is positive or negative).

Agility, innovation, adaptability, or a strong sense of ownership or engagement at work is not something they mandate for their employees. It’s ingrained in the DNA of these organizations. It’s in the consciousness of their people to challenge the status quo rather than to protect it. That’s what they get up for in the morning.

You might argue: “These companies are born into this sweet spot. They are technology companies and therefore don’t have the necessity to adapt.” There’s no need to argue. It doesn’t matter whether they are born into this space or not. The point is this: these change makers will not go away. We simply need to make a choice for ourselves how we want to cope with this new world order.

The changing world order poses a challenge and an opportunity for every one of us. In the years to come, we will need to deal with an entirely new level of uncertainty, volatility and complexity. Many of us — from top leaders to people like you and me — will feel pressured, overwhelmed, or threatened by this change. Unfortunately, when confronted with uncertainty and threat, our knee-jerk reaction as humans is to fight, flight, or freeze. We don’t adapt but react with resistance and fear. And most likely, in those moments, we will revert to Strategy One or Two, but not Strategy Three. We will stop thriving and start surviving.

To effectively deal with the challenges ahead and remain in thriving mode (Strategy Three) doesn’t require us to do more stuff, or to do stuff differently. First and foremost, it requires a change in our consciousness. It requires for us to grow as individuals, so that we are not turning reactive or dominating, but remain authentic, centered, courageous, and aware of our fears — even in those moments when we are faced with an unforeseeable future.